The Afterlife in Cinema

Since its inception, Cinema has been able to explore all aspects of the human condition, even those that are still very much out of our grasp. If you’re religious the notion of the afterlife is more comforting. All major religions have an idea of what happens to your body and soul once you leave this mortal coil. Do you go onto join your dead family, play badminton with the greats of the past, or are you reincarnated into another form of life on Earth. In the past few months I’ve caught a few films that have dealt with the afterlife, most released in the late 80’s/early 90’s and mid 40s, which has reminded me of others.

My journey began with Defending Your Life (1991) which see’s Albert Brook’s Daniel Miller a recently departed after a car-crash (completely his own fault) as he enjoys a birthday present to himself on the highway. He enters a limbo state known as Judgement City where he’s required to defend his past life to a pair of judges. The outcome of which will determine whether he goes onto heaven or has to have another go at life. The concept behind the film is fascinating, and executed well. A comedy with theological ideas that doesn’t take itself too seriously. During his stay in Judgement City he meets Julia (Meryl Streep) practically an angel in her past life whom he falls in love with. However during his trial time and again shows how he’s wriggled out of difficult situations without facing fear in the face, making him a stronger person and somehow worthy of going onto heaven. When he wants to take things to the next level with Julia, he finds himself once more wriggling out of sleeping with her. Not wanting to spoil what he has for what could be a lost love who’s almost guaranteed a place on the bus to heaven. He bails miserably. Thankfully the powers that be allow him to test his ability to face fear and make a run for his new love even if it means losing out at the last minute.

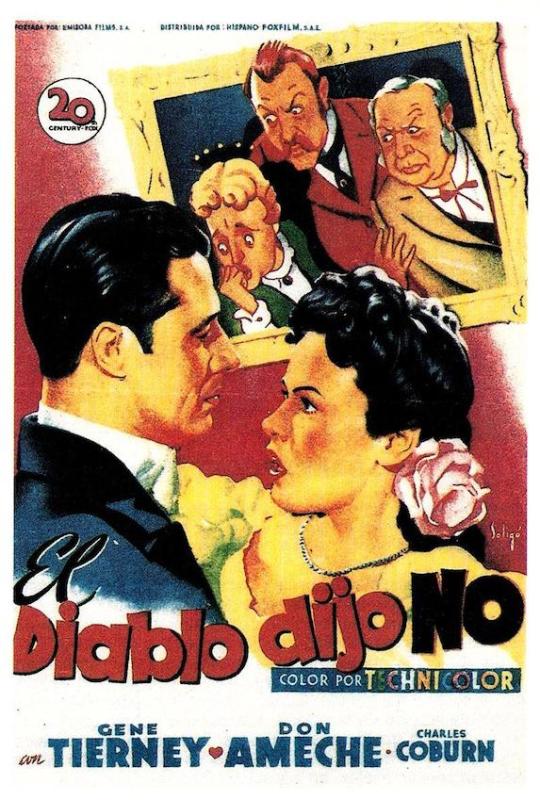

Another example of trial before entering the afterlife can be found in Ernst Lubitsch’s Heaven Can Wait (1943) when an elderly Henry Van Cleve (Don Ameche) recounts his life to a dapper dressed devil in his tastefully decorated waiting room/library. Although the devil (Laird Cregar) is known as His Excellency the audience clearly knows who we are in the company of. The recounting of a misspent youth in an upper-middle class from turn of the century America. We can see that through all the hijinks that deep down he had the love of Martha Strabel Van Cleve (Gene Tierney) who put up with a lot in her marriage to him. Of course in the hands of Lubitsch the threat of spending eternity is hell is dealt with the lightest of touches, during a time when “boys were just being boys”.

Gangsters who actually end up in hell can be given second chances, by literally doing a deal with the devil. In Angel on my Shoulder (1946) sees Paul Muni in dual roles, is shot in the face as double crossed gangster Eddie Kagle landing him straight in hell, complete with fire and brimstone. Through his own complaining and getting in the way he ends up in the office of the devil – Nick (Claude Rains) who offers him a chance to return to his old life. By assuming the body of his double a judge, (who apparently wronged Nick). Asking him to kill his own killer. It’s not the best executed film, yet we can see through the love of the judges fiancee Barbara Foster (Anne Baxter) he begins to change his ways, turning away from his old life. Failing in his task he’s brought back to hell a changed person, it doesn’t make up for his past life but teaches the audience under the pressure of the Hays code that if you want to go to heaven you must lead a good life, a bad one will lead straight to hell.

There’s no trial or depiction of hell or heaven in Ghost (1990). Focusing instead on how a death in a relationship effects the departed. When Patrick Swayze’s Sam Wheat is shot in a mugging, he see’s the bright light that beckons him, choosing to ignore it. Wanting closure wanting answers for his abrupt death and closure for his relationship to Molly (Demi Moore) that his death causes. Both need closure in order to move on in life and death. He learns how to operate as a ghost; his abilities and new limitations. A big development comes when he can communicate with wannabe medium Oda Mae Brown (Whoopi Goldberg) who can now unfortunately hear him. What was once just a game is now a real-life burden for the part-time crook. She wants nothing to do with Sam who needs closure in order to pass on. Using the cliches to get to his old friend and murderer Carl Bruner (Tony Goldwyn) who arranged his murder to get into a rich account. All of this is a great big macguffin for Sam and Molly to be reunited in order to say goodbye and bring closure to their relationship. Molly had always been open to his ghostly presence, even curious to meet with Oda Mae who she learns has a criminal record, any chance to see/feel/be with Sam is worth her time.

The suspicion of mediums goes back to David Lean’s version of Noel Coward’s Blithe Spirit (1945). The quirky and eccentric Madame Arcati (Margaret Rutherford) is invited for both research and pure enjoyment to see if and how she can contact the otherside. Her methods are seen to be believed when she accidentally brings over writer Charles Condomine’s (Rex Harrison) first wife Ruth (Constance Cummings) complete with ghostly green make-up to suggest her changed state of being since passing over. Once brought over, we see the lengths she goes to bring Charles back with her and sending his new wife and her replacement mad, in the process. In this instance, the knowledge of knowing that your living loved ones have moved on, leads her not want to leave him again. She’ll go to any lengths necessary. Both Sam and Ruth want to be with their old partners, one is more accepting if their destiny, whilst the other wants their cake and eat it. Life goes on for some, not for others.

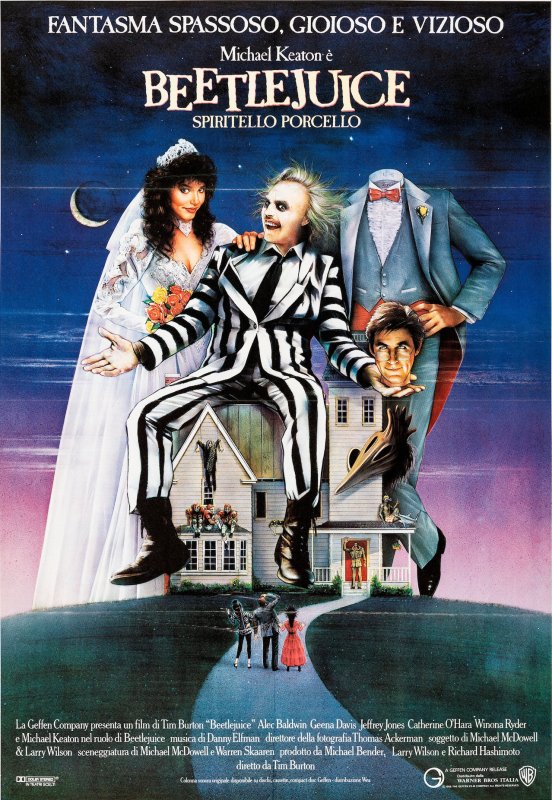

What happens though if a deceased couple don’t want to passover. Tim Burton’s Beetlejuice (1988) sees young couple Adam and Barbara Deetzes (Alec Baldwin and Geena Davis), moving into their New England home, just before they are killed in a freak accident, leaving them in a state of limbo, unwilling to enter the creepy afterlife, they try to haunt the new owners into leave the house – another ghost cliche. Failing to create the atmosphere of a haunted house they call upon the Beetlejuice (Michael Keaton) (don’t say it 3 times) to assist them in getting rid of the new occupants. He fails miserably, instead creating anarchy for everyone. Ultimately the Deetzes and Maitlands decide to live together. The young coupe are so unwilling to passover they decide to live with the living, this is ultimately temporary, they may decide to leave, or wait for them die too.

If the Deetzes and Maitlands can live together, why can’t anyone do it. It takes a certain kind of open minded individual to take on a haunted house such as in The Ghost and Mrs. Muir (1947). Mrs. Lucy Muir (Gene Tierney) does just that when the estate agent has been struggling for years to lease the property. She’s able to connect with Rex Harrison’s Sea Captain Daniel Gregg’s ghost ghost who haunts the home. She sees him more as a companion that she connects with over the course of her life. Unwilling to move out, they come to an agreement that doesn’t make himself known to her daughter. They form a bond of friendship, which throughout he disapproves of her partners, which create comical friction between them both. He decides to leave as he no real connection to the house anymore. Only to return on her death that finally unites them. He loves her from afar, only able to express it really in death when love as we know it ends.

We know that ghosts are the form we are believed to take in death, only those that can’t accept that form or have unfinished business stay behind to resolve it. It’s clear that a number of characters have some in the films I’ve explored here, needing it’s duration to find some closure before moving on. Some long to be with the ones they love most.

David Lowery’s A Ghost Story (2017) depicts a ghost in limbo playing with the inconogtraphy of what a ghost is, distills and reforms it into a playful and profound image that we usually find on the streets every halloween. C (Casey Affleck) simply wears a bed sheet over his body and assumes that role, looming in his marital home. He’s unable or unwilling to accept his own death, where we find grieving M (Rooney Mara) eating a whole pie in one sitting before she eventually moves out and gets on with her life. For a time and the rest of the film C’s ghost occupies the home, which has its own life around him. He becomes a passive observer in the homes history. The audience sits with C under the bed-sheet. This naive image of a ghost becomes so profound. As much as he inhabits the space he doesn’t haunt it, neither does he choose to move through walls or fly. Instead he becomes one with the space, looking on at the occupants that live their, becoming part of the furniture you could say. Here it stands out, unable to move through walls like Sam and the Deetzes learn to. He simply exists in this plane of existence to observe and explore the changing state of the house that he still calls home until suddenly it’s no longer there. Suggesting that we may have stronger connections to places rather than the people we choose to live with and love. C let’s go of M as soon as she leaves the home, he gives up on leaving and starting the afterlife. He’s very much like the Sea captain who for a time is unwilling to leave his old home. Ultimately he dies with the house in this experimental film.

Letting go is hard enough to do in life at times, the past, being wronged by a friend or loved one. But when it stops you moving onto the next life it’s a decision that can haunt you even in death. When pilot Pete Sandich (Richard Dreyfus) in Always (1989) dies in a plane crash, he’s unwilling to accept what Audrey Hepburn’s angel is telling him. He stays to mentor (as best as a ghost can) his replacement Ted Baker (Brad Johnson) at the airbase, whose gets close to Pete’s lover Dorinda (Holly Hunter) whose trying to move on. Pete has to accept that both the living a dead need to move on with the lives in order to be happy. He reluctantly allows this, thus completing his journey to enter heaven.

Cinema has spent more time staying in the world of the living than trying to create a believable heaven – or whatever your religion teaches you. It’s more relatable for the audiences. The need to explore the next life and how we communicate with those who has passed away can be incredibly powerful for some. The bridge to the afterlife comes in the ghosts that are usually unwilling to simply pass over, they have to see their loved ones before they make a final goodbye. Defending Your Life, Heaven Can Wait and even A Matter of Life and Death (1946) look back more on the lives we had, to see if we made the most them, how we affected the lives of others. A film that perfectly sums up that is It’s a Wonderful Life (1946) that shows an alternate world by simply wishing for it, we can see how much we make a difference just by being there. There’s no afterlife there by another life to be seen from a distance. Where ghosts exist in the world of the living, there’s a need – usually a partner that needs to be visited before they can let go of the old life. The depiction of the Afterlife may come in cycles (typically every 30 – 40 years, maybe after the Pandemic finally leaves us behind, we may look at dealing with the overwhelming grief that has yet to be resolved. Looking at the next life allows us to accept our time on this planet is short and our pull to stay here is stronger than we’ll ever know. Only wanting to leave in the knowledge and comfort that we may meet our relatives once more or be reborn and the circle of life continues.

I Need Your Help

I need your help,

I’m working with my local community library in Rothley. For the past few months I have been writing and running a Film Talk. We want to engage with the local community and share my passion for film. It’s early days and we are struggling to connect with the right and steady audience to make this really work.

So far we have discussed It’s A Wonderful Life (1947), A Kind of Loving (1962) and Midnight Cowboy (1969). We have another one lined up, ready and waiting too!

Moving forward I have been working with the Rothley Community Library to put together a short survey (7 questions) for you to answer. Your answers will help Film Talk grow in new and exciting directions.

Film Talk – George Bailey’s Nightmare

On 16th January I presented my first film talk, the first in a series of community based talks about film, looking into films in more detail than before. The first was looking at It’s a Wonderful Life (1947) sharing my insights of the film with the general public. Below you can read the notes from the night.

Tonight I’d like to explore the darker side of It’s a Wonderful Life, (1946), Frank Capra’s Christmas classic that at the time of release got a mixed to luke-warm response from both critics and general public. His first film post WWII, it was also the flagship film for his new production company, Liberty films which he formed with fellow directors and comrades during the war George Stevens, and William Wyler. Both very different directors; Stevens known for his comedies, especially for the Tracy and Hepburn film; Woman of the Year (1942); where the famous affair began. Whereas Wyler had been making a range of films, a few with Bette Davis who he had affairs with. It wasn’t until he released Mrs Miniver (1942) about a middle class British family coping with war on the home front did his career begin to change for the better.

Turning back to Capra, he was a Sicilian immigrant who came to America in 1903 aged six with his family. He would later to move to Hollywood where he would direct a string of very successful comedies during the depression. Moving forward to just before It’s a Wonderful life was released in late 1946, he has spent the last the duration of the World War two, posted in Washington, holding the rank of Major, in command of the U.S. Film core, coordinating projects at home and out on the front line. Most notable colleagues under his command included John Ford, John Huston, William Wyler, who made propaganda films for both public and military consumption.

With exception to John Ford, he was the most successful of the fellow directors, having directed a number of successful comedies, earning himself 3 Best Director Oscars during the 1930’s alone. The films speak for themselves

It Happened One Night (1934) was the first film and comedy to winning the “Big 5” Best Actor, Actress, Writing, Director and Film. The film follows a journalist who will stop at nothing to get an exclusive story of a runaway socialite before her big wedding.

Mr Deeds Goes to Town (1936) won best director, second in a row, and his third nomination. A musician inherits a vast fortune, spending the rest of the film fighting off city slickers who will do anything for it.

You Can’t Take it With You (1938) won Best director and film for his studio Columbia. A rich Families son falls for a daughter from an eccentric family, who in turn lay in the way of the family business’s plans.

Mr. Smith Goes to Washington (1939) most notable for the 12-minute filibuster by James Stewart picked up Best Original Screenplay. A naïve boy ranger’s leader is made governor of his state, when in Washington he finds corruption, not the high ideals who believes in.

All of these films came before Pearl Harbor in December 1942 when he would finish his on-going projects before enlisting. On returning to civilian life, his industry had changed beyond recognition, as much as they wanted him. He wrote in the New York Times about

‘Breaking Hollywood’s “Pattern of Sameness”…This war he wrote had caused American filmmakers to see movies that studios had been turning out “through their eyes” and to recoil from the “machine-like treatment” that, he contended, made most pictures look and sound the same. “Many of the men… producers, directors, scriptwriters returned from service with a firm resolve to remedy this,” he said; the production companies there were now forming would give each of them “freedom and liberty” to pursue “his own individual ideas on subject matter and material”

Five Came Back – Mark Harris – Pg. 419-20

What is this “Pattern of Sameness” that he was reacting to in his article? The article was setting out his opening of an independent studio – Liberty Studios that would produce films unhindered by the moguls. Something that more and more directors were beginning to do. Maybe this “Sameness” was a type of film he was not used to, or produced a negative response in him. Were these the films his contemporaries and even partners in his new venture were all making?

“…his fellow filmmakers, including his two new partners, were becoming more outspoken advocates for increased candour and frankness in Hollywood movies and a more adult approach to storytelling, he flinched at anything that smacked of controversy. Over the past several years he had become so enthralled by the use of film as propaganda that in peacetime he was finding it hard to think of movies in any other way. “ There are just two things that are important,” he told the Los Angeles Times in March. “One is to strengthen the individuals belief in himself, and the other, even more important right now, is to combat a modern trend towards atheism.”

Five Came Back – Mark Harris – Pg. 419-20

His fellow filmmakers were striving for more realism in their work, one response for wanting realism, a stylized realism is Film noir.

“The term “film noir” itself was coined by the French, always astute critics and avid fans of American culture from Alexis de Tocqueville through Charles Baudelaire to the young turks at Cahiers du cinema. It began to appear in French film criticism almost immediately after the conclusion of World War Two. Under Nazi Occupation the French had been deprived of American movies for almost five years; and when they finally began to watch them in late 1945, they noticed a darkening not only of mood but of the subject matter.”

Film Noir – Alain Silver & James Ursini – Pg 10

A new kind of American cinema was flooding into French cinemas.

I’d like to show the nightmare, or alternate reality sequence from the film now. However before I do, I’d like to share what I found in the sequence that fits into what makes a film noir a film noir. There a few themes and visual cues that can be attributed to the genre, each applied to different varieties within the genre, showing how flexible it is.

The Haunted Past –

“Noir protagonists are seldom creatures of the light. They are often escaping some past burdens, sometimes a traumatic incident from their past (as in Detour or Touch of Evil) o sometimes a crime committed out of passion (as in Out of the Past, Criss Cross and Double Indemnity). Occasionally they are simply fleeing their own demons created by ambiguous events buried in their past, as in In a Lonely Place.”

Film Noir – Alain Silver & James Ursini – Pg 15

For George he tries for the majority if the film to escape his hometown – Bedford Falls, which has always pulled him back at the last-minute. His father’s death, marriage to Mary, the Depression, His hearing that stopped him fighting during World War II, until finally he might be leaving to serve a jail sentence for bankruptcy.

The Fatalistic Nightmare – “The noir world revolves around causality. Events are linked like an unbreakable chain and lead inevitably to a heavily foreshadowed conclusion. It is a deterministic universe in which psychology…chance…and even structures of society…can ultimately override whatever good intentions and high hopes the main characters have.”

Film Noir – Alain Silver & James Ursini – Pg 15

You could say that George has been living a nightmare, until he enters into a world created by his desire to not exist.

These are only types of Noir narrative that apply to the film. The look of Noir has been applied to the alternate reality where George enters his Noir Nightmare, the look of the town, now named Pottersville, where we find all the business in town have sold out, part of Potters empire, populated with bars and clubs, another town to drown your sorrows, forget who you are and where you have come from, until reality will ultimately come for payment.

The lighting – Chiaroscuro Lighting. Low-key lighting, in the style of Rembrandt or Caravaggio, marks most noirs of the classic period. Shade and light play against each other not only in night exteriors but also in dimmed interiors shielded from daylight by curtains or Venetian blinds. Hard, unfiltered side light and rim outline and reveal only a portion of the face to create a dramatic tension all its own. Cinematographers such as, John F Seitz and John Alton took his style to the highest level in films like Out of the Past, Double Indemnity and T-Men. Their black and white photography with its high contrasts, stark day exteriors and realistic night work became the standard of the noir style.

Film Noir – Alain Silver & James Ursini – Pg 16

If we look at Out of the Past (1947) which follows a private investigator (Robert Mitchum) who has tried to escape his life, living in a small town as a mechanic, before his old life catches up with him in the form of Kirk Douglas. Here you can see the deep shadow that leaves the characters in almost darkness at times.

Whilst in Double Indemnity (1944) another prime example of the genre we can see how the lights are directed against the blinds, which act more like bars of a jail cell rather than an indicator of the time of day, Light and shadow are used to take us into a dark underworld that is lurking around the corner ready to consume you.

I’m going to play the nightmare sequence now (stills below), afterwards I’ll share some of my observations.

Capra essentially redressed and relight of Bedford Falls? I feel that Capra was reluctant to really delve into the genre he was resisting. He does however replicate the lighting, which is heavily stylised through the exterior scenes and those in the old Granville house, where he had previously (in his living life) threw stones at with Mary. However here it seems more stones have been thrown here, as it’s beyond a ghost house.

Looking at George reaction to the world around him as he begins to realise that this is not his world, the consequences of his not existing has on the world.

Looking at George reaction to the world around him as he begins to realise that this is not his world, the consequences of his not existing has on the world.

I also noticed that it’s the third time that he has jumped/fallen into the water, the first being to save his younger brother Harry’s life, the second as he literally and emotionally falls for Mary, his wife to be.

I also noticed that it’s the third time that he has jumped/fallen into the water, the first being to save his younger brother Harry’s life, the second as he literally and emotionally falls for Mary, his wife to be.

Whilst the third and final fall, is an accidental heroic act that replicates the first time that was for Harry, this time for a stranger, the angel – second-class, Clarence.

Whilst the third and final fall, is an accidental heroic act that replicates the first time that was for Harry, this time for a stranger, the angel – second-class, Clarence.