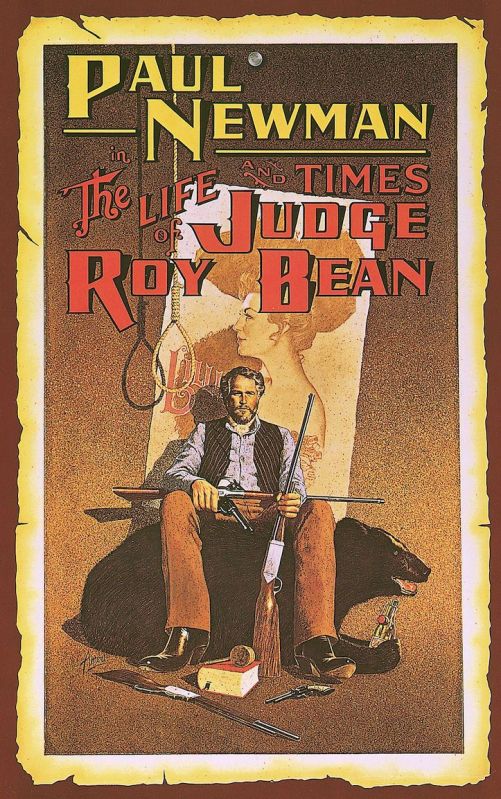

The Life and Times of Judge Roy Bean (1972) & The Westerner (1940)

I’ve been invited to take part in a 3 day blogathon about film biographies, organised by Dr. Annette Bochenek over at Hometowns to Hollywood I’ve decided to choose The Life and Times of Judge Roy Bean (1972). A film that I first noticed in a documentary about the writer/director John Milius who provided the script for John Huston’s film. However just writing about this film wouldn’t do justice to how The Westerner dealt with the historical figure Judge Roy Bean. It’s a great opportunity to see how the depiction of the character has changed in the 32 intervening years. This is how I will frame the review of the 1972 depiction of the frontier judge.

From the opening titles it’s a biography that openly apologises for now being accurate in any shape or form. Instead in keeping with the mythologizing of the figure of Judge Roy Bean who we already knew from William Wyler’s version The Westerner (1940) of the self-made judge as depicted by loveable character actor Walter Brennan. Here in The Life and Times of Judge Roy Bean with Paul Newman in the titular role brings another dimension to the role and the figure. With a 5 other depictions in the intervening years, Newman has a lot to draw on or ignore. Where would he go in bringing this figure alive. From the opening scenes he makes quite the impact on the quiet little one-horse town of Vinegaroon, West of the Pecos. A saloon worth of men and women assault, rob and tie him to a horse by a noose. His criminal infamy is enough to cash in on his wanted poster. The rope is too worn to do the job properly, not even being able to rise from the dead like Clint Eastwood he breaks free and nursed by local Mexican Maria Elena (Victoria Principal). The white town that he meets may want him dead, but the local Mexicans see something in his worth saving.

His escape from death is almost Christ-like, almost resurrected from certain death he takes the law into his own hands and deals out his own form of justice. First a dose of revenge that chews up the saloon. He’s not a man to be tested after almost meeting his maker. In reality by the time he reached Vinegaroon, a town he actually founded, he had been bought out of Beanville a Mexican slum where he owned a saloon. A young wife and 4 children. He had already lived a good life, with some criminality before he arrived at the famous boom town he would remake in his image and in John Huston’s film, one of the few facts they kept. Bean has been reshaped in Cinema’s image as a violent figure driven by dreams of grandeur that allowed him to become larger than life. Roy Bean has a lot in common with Little Big Man (1970) that constructed a fictional life of cliche for Jack Crab (Dustin Hoffman) that simply enjoyed poking fun at the genre whilst taking a closer look at the truth of the treatment of Native Americans.

His rise to the position of Judge is made upon a law book that he treats like a bible, making himself a god-like figure who wants to do only good, taking ownership of the land around him, treating the Mexicans kindly in thanks for his own treatment and rise to self-made power in Vinegaroon. A self-made man rising from the ashes of violence to be a Judge of the law under his interpretation. Could he have been inspired by the passing preacher Rev LaSalle (Anthony Perkins) who tests his morality. It’s LaSalle who buries Beans victims and reads over them. Bean sees them as collateral in his rise to power and being remade in the image of the law – not Lord. He starts out by employing 4 outlaws to become his Marshalls that keep the peace and find criminals to try in Beans court. There’s little real sense of justice, you’re guilty as charged with chance of proving yourself innocent. The word, the law of the Bean in his four disciples who ride out to ensure it’s kept behind the power of a badge.

What follows is a series of events that mirror Little Big Man who goes through his phases in flashback, for Bean it’s those that visit and begin to populate Vinegaroon as is becomes a boomtown by the close of the century. By which time in reality the judge would die in 1903. His whole life is moved forward and rewritten to begin afresh after entering that small bar that becomes his courtroom. The arrival of wagon full of prostitutes that want to set-up a brothel are given a second chance at a decent life – he’s a preacher who baptises them by pairing them off with each of the marshalls, whilst the 5th is forced to ride off like pimp (Jack Colvin) who himself is given a chance to start over. By pairing them off with sex-starved marshalls is more a treat for the men than a fresh start of a decent life.

A small cameo from director Huston as real life mountain man Grizzily Adams brings a new dimension to Bean, we’re lead to the comparison of Teddy Roosevelt, whose thought to be the best President they ever had at the time by the narrator/Tector Crites (Ned Beatty). Bean isn’t afraid of the bear that’s left by the mountain man, not really taming it but becoming it’s equal (before caging it up as an circus attraction) Both Adams and Bean are men who tamed their environment, became masters of all they surveyed.

Through all of these mad-cap encounters it’s a love for singer Lillie Langtry that remains strong, raised to a higher plain, even above the position of women, a goddess. Something that Ava Gardner has been depicted as earlier in her career (One Touch of Venus (1948)). A woman that he idolises above all else, she’s more than human to him. He fall from grace is when he becomes human for a night, a simple fan who wants to meet his idol. Before coming home to see his empire and position have been usurped by lawyer Frank Gass (Roddy McDowell) who begins to democratise the town, before falling to the draw of oil that’s discovered.

Bean is forced to leave, his lover having died in childbirth, his empire destroyed in his absence. This is when the film starts to go into pure fantasy – As the passing of time progresses in montage during the early life of his abandoned daughter Rose (Jacqueline Bisset) the end of WWI, prohibition and the discovery of oil that brings us back the Vinegaroon where Gass has become a Plainview figure, driven by avarice, wanting the relic of the wiped of the face of the earth. Of course no such thing happens, instead a nonsensical fight between cowboys and the police unfolds, as untame West fights progress one last time before giving way. Except progress loses out to bring a more factual account of how Langtry finally arrived in Vinegaroon. Probably the only shred of truth in a film built upon the mockery of myth-making. It was a comical journey filled with actors that we know and love, breathing life into a genre that was dying in the face of changing tastes, a healthy dose of mockery was needed to see the genre and it’s foundations in a new light. Encapsulating how the West was formed, a lawless way living that was gradually civilized, the lawless elements stamped out in the way of progress and 20th century greed that has become the norm today.

It’s honestly always a pleasure to revisit a classic western, especially when you have a good excuse. It reminds me that the Western genre has the ability to reshape American history to suit the needs of the time. Characters like Judge Roy Bean become villians, whilst history records he did hand out some unorthodox sentences he was not as keen to hang those who were tried in his court as easily as William Wyler’s film suggests. He did in fact favour issue more fines than hanging the defendants.

Roy Bean isn’t even the centre of this film, it’s posed as a Gary Cooper vehicle that sees him ride into a part of the country in dispute between homesteaders and cattlemen. Once again it’s a fight for freedom of movement for the biggest business in the country, it must roam free to ensure the prosperity of the nation. It’s the 1880’s, the western frontier is closing within the next 15 years now, fencing is becoming more common as farming begins to take hold. It’s not just beef that Americans want, a growing nation needs other food to grow up healthy. The Westerner on the surface is another tale of cattlemen vs. homesteader, allowing a stranger to ride in and run circles around the powerful little man that is Bean. Cooper’s more educated Cole Harden a stranger to the legal climate can test it’s legitimacy.

We see how a kangaroo court has take hold in Vinegaroo, again West of the Peco’s, delivering deathly sentences with ease, Bean’s done this for years, just as we see as Life and Times suggests, both have a vast graveyard to boast of. When a supposed horse thief rides in Harden he’s position is tested. Assisted by Jane Ellen Matthews (Doris Davenport) who knows what Bean is like, rides to Harden’s defence. It’s not enough, even the horse outside doesn’t help. It’s both comical and depressing. Harden soon discovers Bean’s one weakness, it’s plastered all over the walls of the saloon/courthouse – the actress Lily Langtree whom he adores to a fault. John Huston’s set-decoration is far more restrained. This infatuation is used to see Harden escape the noose and enter into his inner circle, the promise of seeing a lock of Langtree’s hair is a promise he can’t pass upon, Bean is naive to this manipulation.

Walter Brennan’s take on the role is that of a man-child, especially around Harden. His “connection” to his idol is something he can’t ignore. However he’s still not a man to be underestimated. As much as his attention can be diverted he’s a cattle man and nothing waver that support. Brennan maybe in a supporting role, yet his presence is felt elsewhere, the homesteaders fear him and what he represents to them. The fire that he instigates just shows how powerful he can be. In reality he was more bothered about the coming of the steam train than the threat of farmers, putting his life on the line to avoid his court being flattened. He’s not the irascible drunk that Newman portrays, or beholden to a written book of laws, by the time we meet him in The Westerner he has written his own laws. Brennan balances the two side of Bean so that we both come to feel sorry for him as much as we fear him. Leading to his ultimate demise just as he meets his idol. Something that history records he never got the chance to do. This encounter is the stuff of pure cinema, as it rewrites history to deliver a dream like ending to an figure from history that made an impression on history and those around him. 30 years later we see the same character in a far different light, he still holds court – literally yet his dominance is tested to a greater degree, he’s given a bigger canvas to play upon which is more fun to watch yet lacks the charm of cinema’s first interpretation of Bean.

Please check out other contributors to this blogathan here. It’s been a pleasure to have been asked to take part. It’s always fun to write a film, finding new angles to explore the Western genre, which heavily informs my own work. Film will naturally distort the truth for entertainment value, and to be honest some parts of history do need to be shaken up so we can engage with, to explore the facts for ourselves and understand what really went on behind those who inspired the films we enjoy today.